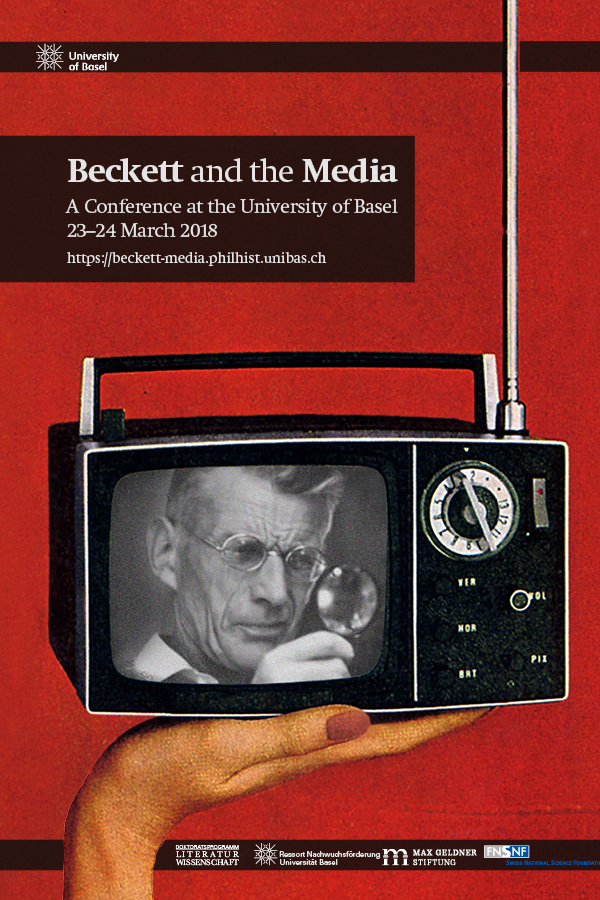

Beckett’s Media System | Conference “Beckett and the Media” (University of Basel, 23-24 March 2018)

Over the years, Beckett Studies have undergone multiple transformations: from early existentialist approaches to post-structuralist interventions, to performance-oriented studies, and genetic criticism. The last two decades have seen a surge in scholarship that probes the relations between Beckett and media technologies. This conference brings together some of the leading Beckett scholars who have focused on the nexus between Beckett and media while opening its doors to media theorists from outside of Beckett Studies who have a strong interest in his work.

Over the years, Beckett Studies have undergone multiple transformations: from early existentialist approaches to post-structuralist interventions, to performance-oriented studies, and genetic criticism. The last two decades have seen a surge in scholarship that probes the relations between Beckett and media technologies. This conference brings together some of the leading Beckett scholars who have focused on the nexus between Beckett and media while opening its doors to media theorists from outside of Beckett Studies who have a strong interest in his work.

Conceiving of media in broad terms (which include technologies, devices and apparatuses, sounds, images and texts, codes and notation systems, or the voice and the body), we would like to foster an approach that grasps media as a convergence of communicational, technical and aesthetic spheres and that is attentive to media both as environments and as operations. The conference is designed to explore the importance of media in Beckett by asking questions such as:

- What are the benefits of seeing Beckett’s work in several media in their interconnectedness?

- What new insights emerge when we view Beckett’s work as an engagement with developing media technologies and, correspondingly, alternative, competing forms of communication and representation?

- How can we address the question of media plurality in Beckett’s output, and what is the significance of this plurality?

- Can we outline Beckett’s general media aesthetic relying on its literary, theatrical, radiophonic, filmic, and televisual manifestations?

- What kind of strategies (of manipulation) does Beckett employ to stage the agency of the medium?

- How does a focus on media inflect questions of memory, perception and cognition, the body, and identity formation in Beckett?

- Can we develop a specifically Beckettian conception of media?

- How innovative and how radical was Beckett as a media artist, and to what extent is he still our contemporary in his engagement with various media?

The conference aims to probe the relations between Beckett and the media on at least five levels, welcoming case studies, theorizations, and other approaches too: a) Beckett’s work in different media (film, TV plays, radio plays, vidéocassette), b) deployment of media and technologies in theatrical productions of Beckett’s texts, c) references to media in the fictional worlds of his texts, d) media-theoretical considerations of Beckett, and e) digital humanities in Beckett Studies.

Beckett and the Media ¦ Program

Friday, March 23

|

13.45-14.00 |

Welcome and Opening |

|

14.00-15.15 |

Screening & Talk Nicholas Johnson, “Intermedial Play, Virtual Play: Beckett in Digital Culture” Moderation: Philipp Schweighauser |

|

15.15-15.45 |

Coffee Break |

|

15.45-17.30 |

Panel 1: Media Aesthetics Ulrika Maude, “Beckett, Media and Machine Age Form” Balazs Rapcsak, “Beckett the Spiritist, or: Breath as ‘Media Play’” Armin Schäfer, “Beckett’s Exhausted Media” Chair: Ridvan Askin |

|

17.30-18.00 |

Coffee Break |

|

18.00-19.15 |

Panel 2: Media Transfers Mark Nixon, “Samuel Beckett and Newspaper Culture” Dirk Van Hulle, “Editing Beckett in Digital Media” Chair: Melanie Küng |

|

20.00 |

Conference Dinner |

Saturday, March 24

|

9.30-10.45 |

Keynote Wolfgang Ernst, “Techno-Drama / Techno-Trauma: In-between Theatre as Cultural Form and True Media Theatre” Moderation: Balazs Rapcsak |

|

10.45-11:15 |

Coffee Break |

|

11:15-13:00 |

Panel 3: Screen Technologies Julian Murphet, “Understanding Quad” Philipp Schweighauser, “Angles of Immunity: Beckett’s Film” Jonathan Bignell, “Black Screens: Beckett and Television Technologies” Chair: Daniela Keller |

|

13:00-14:30 |

Catered Lunch |

|

14:30-15:45 |

Panel 4: Radiophonics Gaby Hartel, “Out of the Dark or from the Visual World? Beckett’s Use of Acousmatics in his Radio Works” Pim Verhulst, “Beckett’s Remediated Bodies: Intersections of Radio and Theatre” Chair: Jérôme Laubner |

|

15:45-16:00 |

Closing Remarks |

Beckett and the Media ¦ Abstracts

Jonathan Bignell ¦ Black Screens: Beckett and Television Technologies

This paper will analyse how the aesthetics of black in Beckett’s dramas for TV illuminate recent theorisations of the significance of texture in television and film, and histories of television production and reception technologies. The argument will begin with a comparison between Walter Asmus’s 1986 television version of Was Wo [What Where] and his 2013 reworking of the same drama for the screen. Asmus’s earlier version was broadcast in a 4:3 ratio of width to height, whereas the recent version is in 16:9 aspect ratio, affecting composition and the relationships between lit and unlit space on screen. Beckett wrote the word “Black” across a diagram of the TV screen in his production notes for Was Wo, and great efforts were made by staff at SDR in Stuttgart to control the lighting of the faces and the blackness of the rest of the image. The earlier version was shot on video and broadcast in 625 line video, limiting contrasts between greys and blacks. The 2013 What Where is in HD digital format, enhancing image clarity but stretching the limits of TV technology for the representation of black. The paper will explain how Beckett’s earlier screen dramas of the 1960s and 1970s had also exploited and challenged the video and film technologies used to produce them. By focusing on black, the paper explores the significance of unlit space and texture in TV versions of Beckett’s screen work produced at different times. These changing television technologies affect how viewers can make sense of visual textures and apparent depth in the dramas. Beckett’s TV work uses the apparent nullity of black to draw attention to the representational capabilities of the TV screen, linking visual style with the materiality of the television medium.

Wolfgang Ernst ¦ Techno-Drama / Techno-Trauma: In-between Theatre as Cultural Form and True Media Theatre

If we combine sound philology and the archival contextualization of Beckett’s oeuvre within his contemporary media culture with a radically media archaeological reading of the one-act drama Krapp’s Last Tape, we will discover a different poetic emerging from within the media-technological sphere of magnetophony (its ‘sonicity’).

A non-historicist reading of Krapp’s Last Tape does not circle around the rigid denominator ‘Beckett’ and its performative idiosyncrasies as an individual author but understands the beckett drama as an operational function of the epistemic challenge posed by the manipulations of tempor(e)alities by electro-acoustics around the 1950s / 1960s. What happens when psychic ‘latency’ becomes magnetic signal recording? Not only is the configuration of a human protagonist (Krapp) and a high-technological device (the magnetophone) a microsocial configuration in the sense of Actor-Network Theory or an ensemble in Simondon’s sense, but the close coupling of the human and the machine on the stage requires a more rigorous analysis (in the Lacanian sense) of the cognitive, affective, even traumatic irritations induced in humans by the signal transducing machine.

This talk will thus attempt to zoom in on the media message of Krapp’s Last Tape, and its approach is inductive in two ways: on the one hand, electro-magnetic induction is the technological condition (the arché) of possibility (in Kant’s / Foucault’s / Kittler’s sense) of the phonographic drama at stake in Krapp’s Last Tape, and on the other hand, in the sense of idiographic identifications of the real media theatre.

Gaby Hartel ¦ Out of the Dark or from the Visual World? Beckett’s Use of Acousmatics in his Radio Works

Our sense of hearing has developed to inform us about things we do not see. But how do we really perceive sounds? Do we perceive them as coming from a definable source or as potentially abstract aural emanations of an unseen reality? Since the beginning of radio art there has been much debate about this question, as early art theorists, composers, and broadcasters such as Kurt Weill and Rudolf Arnheim welcomed the immateriality of the medium and its potential to teach us an appreciation of art that is connected to the human body but at times unrelated to the physical world as we behold it with our eyes. This talk probes Beckett’s thinking and artistic practice.

Nicholas Johnson ¦ Intermedial Play, Virtual Play: Beckett in Digital Culture

This presentation will explore and contextualize some documentation from the ongoing Intermedial Play practice-as-research project, which is an exploration of Samuel Beckett’s Play (1963) through digital culture. Some video will be presented from the first experiment (14 April 2017), a version that emerged from conversations relating to creative possibilities for a PTZ (Pan-Tilt-Zoom) robotic teleconferencing camera and control unit. Conceptually exploring the similarity between such a camera (designed for surveillance applications) and the “interrogator” light of Beckett’s script, this experiment was streamed to an audience sitting in a different room, raising questions of simultaneity and “live risk” that are generally absent from digital adaptations. The second experiment, currently ongoing, relates to a user-centred FVV (Free-Viewpoint-Video) — a variety of VR (Virtual Reality) — version of Play.

This technological reinterpretation of Play is an exploration of the new cultural subjectivities imposed on humans by new technologies of presence in digital culture. Though partly inspired by Anthony Minghella’s version of Play that was produced for the BBC’s compilation Beckett on Film (2001), our versions elicit the specificities of new, real-time, digital telepresence technologies, thereby offering a fresh digital augmentation of both Beckett’s famous script, as well as a Beckettian response to these technologies.

Ulrika Maude ¦ Beckett, Media and Machine Age Form

In 1936, Beckett read Rudolf Arnheim’s book, Film, which had been translated into English three years earlier from the German original, Film als Kunst (1932). In the book, Arnheim laments the introduction of sound and colour to film, arguing that the power of the medium resided precisely in the strangeness generated by its limitations, namely in the uniquely visual nature of silent film. Beckett, who like Arnheim was an advocate of silent film, took the limitations not merely of film but of the other media he worked in as the starting point of his aesthetic. His interest was less in what a medium could achieve than in where its boundaries lay. This is one dimension of Beckett’s ‘art of impoverishment’. By pressing each medium to its formal limits – to the point at which it threatens to spill over into another form – Beckett questions, while also seeming to insist on, the formal particularity of the medium in question. Beckett’s interest in technology, and in the possibilities of the different media in which he worked, grows partly out of the analogies he finds between the machinic and the human. Here, too, he is interested not in what a subject can do but in the limitations of perception, of understanding, and most markedly of agency, intentionality, and free will. This paper will attempt to map the syntax of Beckett’s media aesthetic, and look at the wider implications of his Machine Age multimedial work.

Julian Murphet ¦ Understanding Quad

The electronic interlaced raster scan that composes a televisual ‘image’ was relayed to the cathode ray beam by way of an analogue signal from the broadcast video source. That signal amounted to a set of instructions, telling the beam how to behave as it was pulled in a line, magnetically, across the back of the phosphor-treated CRT screen from left to right, before snapping back left again to trace the next line down, and so on: specifically, the signal informed the beam how intensely to transmit at each point of its passage, with what colour electron guns, and with what velocity and refresh rate. These instructions worked, irrespective of the imaginary ‘content’ of the image temporarily formed thanks to phosphor persistence, moiré induction, and retinal retention. They worked on the basis of an electronic arrangement of post-human speed, and the inbuilt conservatism of the psychological apparatus; as McLuhan puts it, “The TV image offers some three million dots per second to the receiver. From these he accepts only a few dozen each instant, from which to make an image.”

Beckett’s Quad is still the most extraordinary work of art composed for the televisual medium, though what is most remarkable about it is scarcely ever discussed. In a word, this is still the only major work for the ‘small screen’ written in an act of imaginative sympathy with the raster scan itself: an impersonal set of instructions about how to move across and around a rectangular space, conjuring images out of mathematically controlled movements. In this paper, I will look deeper into the implications of Beckett’s intuitions with regard to the analogue electronic arts as arts of time set to the measure of inhuman speeds and rhythms.

Mark Nixon ¦ Samuel Beckett and Newspaper Culture

Samuel Beckett is often seen as representing ‘high culture,’ as being a writer who moved within intellectual circles and whose work eschews mass consumption. A reader report on the novel Molloy by the publishing house Secker & Warburg in the late 1940s epitomises this opinion, stating as it does that this book would only appeal to people who will read it for ‘snobbish’ reasons. Indeed, Beckett was mainly published by literary magazines and reasonably small and exclusive publishing houses, whose catalogues did not appeal to the general reading public. Yet as this paper reveals, Beckett was also connected with (daily and weekly) newspapers as well as non-literary magazines such as The Spectator, a form of mass media that reached a greater number of people. In engaging with the topic of Beckett and newspaper culture, this paper will first of all show how Beckett was an avid reader of newspapers, regularly reading papers such as the Irish Times, The Sunday Times and the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung in the 1930s. After the War, Beckett read the daily left-wing French newspaper Combat, and urged his friends to do the same. Secondly, Beckett, like Joyce before him, sourced material from newspapers, and as such there are several references to newspapers in his texts. And finally, this paper will examine the neglected fact that Beckett’s work was actually published in newspapers, from the poems ‘Dieppe’ and ‘Saint-Lô’ in the Irish Times (1945 and 1946), the story Ill Seen Ill Said in The New Yorker (1981), to the penultimate work ‘Stirrings Still’ in The Guardian (1989). Drawing on archival and other sources, this paper will on the whole examine the intersections between Beckett’s work, newspaper and mass media.

Balazs Rapcsak ¦ Beckett the Spiritist, or: Breath as ‘Media Play’

Breath does not feature any technical objects on the stage, as many of Beckett’s theatre plays do, and the use of technical apparatus in its performance is limited. However, a close consideration of its aesthetic as well as aspects of its genesis and production history helps us to situate it in a discourse network and describe the layers of its medial constitution, while revealing the surprising complexity of a play that has been characterized as “simplicity itself.” Arguing for the necessity of a methodological distinction, I offer a rhetorical analysis of the script and a media aesthetic analysis of its realization in performance to demonstrate that there is a dual ‘spiritism’ at work in the play, which I try to illuminate by developing and contrasting the notions of hermeneutic spectrality and technological spectrality. After focusing on the text’s implicit tension between technicality and figurativeness, I attempt to show that the play is conceived around a relationship of untranslatability between script and performance, which allows me to trace a sequence of medial transpositions and interferences within, between and beyond script and performance. In the next step, I place these insights in the context of the first production of the play as part of the revue Oh! Calcutta!, claiming that the appropriation and the seemingly banal scandal that ensued is not (only) a story of abused trust but was, in fact, inscribed in the medial constitution of the play itself and cannot be separated from it; and, consequently, that there is a media drama unfolding not only in but also around the play. Reaching my conclusion, I advocate a synoptic view of genetic and production history, theatrical and reading experience, as well as the technical and socio-cultural factors involved to facilitate a better understanding of how Breath became a ‘media play.’

Armin Schäfer ¦ Beckett’s Exhausted Media

My talk aims to comment on Gilles Deleuze’s substantial argument that the notion of exhaustion is at the core of Beckett’s works. In a first step, I would like to discuss the psychophysiology of movements in Beckett. There are movements that fade until they stop and movements that go on and on and on. These movements are governed by the laws of physiology; it is inevitable that everyone gets tired after performing an activity, although everyone gets tired in an individual way. Under normal conditions, the subject is capable of governing itself. It is possible to counteract fatigue to a certain degree by resting, eating, drinking, and sleeping on the one hand, and by regular training and the effort of will on the other hand. But in the end, fatigue that eventually leads to sleep is protecting the subject against exhaustion. While the tired person is able to resume activity in a predictable way, it is uncertain whether and how the exhausted one can ever do so. Under the influence of passion, however, a performance can continue until exhaustion. The exhausted subject will do what is still possible by performing without consideration and regard to personal interest. In a second step, I will ask how Beckett exhausts language and fiction. One example is the enumeration of possible combinations until one gets tired of them. Beckett’s language uses series of antitheses, oxymora, paradoxes, and contradictions where statements are made, inferences derived, and negations of inferences produced, and these negations are, in turn, negated. Another example is how fiction keeps amputating the stories until they fade and extinguish the potential of narrating a plot. In a third step, I will question the function of media and argue that the concept of media in Beckett has to be defined neither as form or device of representation such as theatre or film nor as a technical apparatus such as print or radio nor or as a symbolic system such as alphabetic writing, but, rather, as the means to make something visible and audible. While Beckett’s media give us representations of the exhausted subject, they are also exhausting the potential of a situation by exhausting its own possibilities, i.e. by making audible and visible what could be called, according to Deleuze, a percept, that is an acoustic or optical sensation that stands for itself.

Philipp Schweighauser ¦ Angles of Immunity: Beckett’s Film

The historical setting of Beckett’s Film in 1929 is conventionally related to the significance of that year in the history of film. 1929 not only saw the premiere of Luis Buñuel und Salvador Dalí’s groundbreaking Un chien andalou (to whose most famous scene Film’s opening shot of O’s eye pays homage) but also marks the almost complete transition of Hollywood from silent films to talkies (which reverberates in Film in the only sound we hear: a woman’s ‘sssh!’). But Beckett’s use of the device of the ‘angle of immunity’—the 45° camera angle whose three breaches in the movie induce the “agony of perceivedness” that O seeks to avoid—suggests an additional historical context. The ‘angle of immunity’ is not a technical term in filmmaking, so the question is why Beckett opted to use ‘immunity’—a term that belongs to multiple social realms: medicine, anthropology, religion, morality, politics, and the law. It is, perhaps, a historical coincidence that Film is set in a year significant in the history of immunology. As Arthur M. Silverstein notes in A History of Immunology, “It was in 1929 that Louis Dienes first showed that tuberculin-type hypersensitivity was not restricted to substances of bacterial origin. He injected egg albumin directly into the tubercles of tubercular animals and demonstrates that they would then develop typical ‘delayed’ hypersensitivity skin reactions to the bland protein itself.” Delayed hypersensitivity is one of those ‘heretical’ immunological phenomena that could not be explained with the help of the humoralist immunological dogma of Dienes’s time, which considered the antibodies circulating in the body’s humors (mainly blood and lymph) the sole agents of the human immune response. It would take thirty years until the immunological revolution took off, which prompted an awareness of the systemic complexity of human immunity, recognized the crucial role played by cells, and, most significantly, defined immunology as the ‘science of self/not-self discrimination.’ Driven by the publication of Frank Macfarlane Burnet’s The Clonal Selection Theory of Acquired Immunity (1959), this revolution was well underway as Beckett was shooting Film in 1964. Both the historical setting of Film in 1929 and its production in the early 1960s prompt me to inquire into the medical meanings of ‘immunity’ in a film whose damaged protagonist, dilapidated setting, and production in the sweltering heat of New York in July prominently raise issues of health and disease. I supplement this inquiry into the medical meanings of Beckett’s ‘angle of immunity’ with an exploration of the concept’s social significance. Drawing on Jacques Derrida’s and Roberto Esposito’s reflections on community, immunity, and autoimmunity, I note that O’s flight in Beckett’s Film is not merely a flight from perception but also a flight from community—most prominently from the community of the film’s initial street scene, wich Ross Lipman restored in the 2010s. This flight from community, I argue, manifests the destructive, autoimmunitary logic of the self/not-self dichotomy that the immunological revolution succeeded in placing at the heart of immunology as Beckett was shooting his film.

Dirk Van Hulle ¦ Editing Beckett in Digital Media

Given the fact that Beckett was very open to new media, such as radio and television, it is only fitting that this openness also characterizes the posthumous care we take of his texts. This means that we should seriously consider the need but also the consequences of editing Beckett’s texts in the digital age. The digital medium enables us to present aspects of Beckett’s works that used to be known to only the lucky few who had been able to travel to the Beckett archives around the world. Beckett donated many of his manuscripts to friends and these documents ended up in more than a dozen different holding libraries. If one wished to study the writing process of, say, Krapp’s Last Tape, one had to travel to various places in the US and the UK. By scanning these manuscripts, we were able to digitally reunite the dispersed manuscripts in the Beckett Digital Manuscript Project, which is available online since 2011 (BDMP, www.beckettarchive.org). Editing this material, however, presents us with many challenges, such as the choice between a ‘teleological’ and a ‘dysteleological’ editorial approach: should we present Beckett’s manuscripts as documents leading to particular publications, or should we (also) present them as traces of moments in the creative process when Beckett did not yet know where his writing was heading? And how should this digital genetic edition relate to the planned critical edition of Beckett’s complete works (on paper, i.e. another medium)? The proposed paper starts from the BDMP as a case study to critically discuss these challenges of editing Beckett’s works, both in printed form and in digital media.

Pim Verhulst ¦ Beckett’s Remediated Bodies: Intersections of Radio and Theatre

When Billie Whitelaw was rehearsing Footfalls in 1976, she asked Beckett: ‘Am I dead?’, to which he replied: ‘Let’s just say you’re not quite there’. This ambiguous presence of the body in the play goes back to a precedent twenty years earlier, namely the character of Miss Fitt in the radio play All That Fall, who tells Maddy Rooney: ‘I suppose the truth is I am not there, Mrs Rooney, just not really there at all’. Though written two decades apart, both instances refer to the Jung lecture that Beckett heard in 1935 about a girl not being ‘properly born’. Yet there is also an underlying, medium-specific connection between Footfalls and All That Fall. When Beckett started writing for radio, he made a clear distinction with theatre: the one was intended for voices, the other for bodies. In the mid-1950s, however, a convergence began taking place, as the body in Beckett’s theatre was gradually reconceptualized under the ‘disembodying’ influence of radio. His earlier comments notwithstanding, the body is a continuous though sometimes problematic presence in Beckett’s radio drama. Starting with All That Fall and Embers, this paper illustrates how a process of ‘remediation’ accounts for the radical and innovative ‘re-imbodiment’ of Beckett’s late theatre. In the definition of Bolter and Grusin (1998), ‘remediation’ is understood as an assimilation of older media by new ones. In Beckett’s case, the reverse happens, as theatre adopts characteristics of radio, innovating that older medium in the process. As Julian Murphet (2009) and David Trotter (2013) have argued, it is precisely this responsiveness to cultural codes of new technologies that determines the robustness and longevity of a medium, in this case the poetry and prose of modernism. What is true on the macro-level of a global literary movement, also holds on the micro-level of an individual literary oeuvre, which explains why Beckett is one of the great inter- and multimedial authors of the twentieth century.

Bios

Jonathan Bignell is Professor of Television and Film in the Department of Film, Theatre & Television at the University of Reading. His work on Beckett includes his book Beckett on Screen: The Television Plays and articles in Samuel Beckett Today/Aujourd’hui and the Journal of Beckett Studies. Jonathan has published chapters on Beckett’s screen drama in the collections Writing and Cinema (which he also edited), Beckett and Nothing (ed. Daniela Caselli) and Drawing on Beckett (ed. Linda Ben-Zvi). Currently he is working on a collaborative project documenting and analysing Harold Pinter’s work for the stage, screen and broadcast. Jonathan is a Trustee of the Beckett International Foundation and a member of the Centre for Beckett Studies at the University of Reading.

Academically trained as a historian (PhD) and a classicist (Latin Philology and Classical Archaeology) with an ongoing interest in cultural tempor(e)alities, Wolfgang Ernst grew into the emergent technology-oriented “German school” of media studies and is Full Professor of Media Theories in the Institute for Musicology and Media Science at Humboldt University in Berlin since 2003. His academic focus has been on archival theory and museology, before he devoted his attention to media materialities. His current research covers media archaeology as a method, theory of technical storage, technologies of cultural transmission, micro-temporal media aesthetics and their chronopoetic potentials, and sound analysis (“sonicity”) from a media-epistemological point of view. Publications in English include Digital Memory and the Archive (2013); Chronopoetics: The Temporal Being and Operativity of Technological Media (2016); and Sonic Time Machines: Explicit Sound, Sirenic Voices and Implicit Sonicity in Terms of Media Knowledge (2016).

Gaby Hartel is an independent culture journalist, writer for the radio, and literary translator. She wrote her PhD thesis on Samuel Beckett as a visual artist and published several articles on him. Since 2000, she co-curated several exhibitions, including “Samuel Beckett/Bruce Nauman” (Kunsthalle Wien, 2000). She edited and translated Samuel Beckett, Das Gleiche nochmals anders: Texte zur bildenden Kunst (Suhrkamp 2000), co-wrote (with Carola Veit) Samuel Beckett: Leben, Werk, Wirkung (Suhrkamp 2006), and co-edited (with Michael Glasmeier) The Eye of Prey: Becketts Becketts Film-, Fernseh- und Videoarbeiten (Suhrkamp 2011).

Nicholas Johnson is Assistant Professor of Drama at Trinity College Dublin, as well as performer, director, and writer. He co-founded the Beckett Summer School at Trinity College Dublin and facilitates theatre workshops around the world. Recent theatre work includes The David Fragments (Dublin/London 2017); Beckett’s First Play (Dead Centre, 2017); Cascando (Pan Pan, 2016); No’s Knife (Lincoln Center, 2015); and Enemy of the Stars (Dublin/Fez, 2015). He co-edited the Journal of Beckett Studies special issue on performance (23.1, 2014) and co-founded the Samuel Beckett Laboratory with Jonathan Heron (Warwick). In 2016 he held a visiting research position at Yale University.

Ulrika Maude is Reader in Modernism and Twentieth-Century Literature at the University of Bristol. She is the author of Beckett, Technology and the Body (Cambridge University Press, 2009) and Samuel Beckett and Medicine (Cambridge UP, 2018), and co-editor of a number of books, including Beckett and Phenomenology (Continuum, 2009); The Cambridge Companion to the Body in Literature (Cambridge UP, 2015) and The Bloomsbury Companion to Modernist Literature (Bloomsbury, 2018). She is a member of the editorial board of the Journal of Beckett Studies and the journal’s Review Editor.

Julian Murphet is Scientia Professor of English and Film Studies at the University of New South Wales in Sydney, Australia. He has published Faulkner’s Media Romance (Oxford, 2017), Multimedia Modernism (Cambridge, 2009), and Literature and Race in Los Angeles (Cambridge, 2001), among other things. He has co-edited many collections of scholarly work, including Sounding Modernism (2017), Rancière and Literature (2016), Faulkner in the Media Ecology (2015), and Modernism and Masculinity (2014). He edits, with Sean Pryor, the journal Affirmations: of the modern. He is a Fellow of the Academy of the Humanities in Australia.

Mark Nixon is Associate Professor in Modern Literature at the University of Reading, where he is also Co-Director of the Beckett International Foundation. With Dirk Van Hulle, he is editor in chief of the Journal of Beckett Studies and Co-Director of the Beckett Digital Manuscript Project. He is also an editor of Samuel Beckett Today / Aujourd’hui and a former President of the Samuel Beckett Society. He has published widely on Beckett’s work; recent books include Samuel Beckett’s Library (with Dirk Van Hulle, Cambridge UP, 2013) and the critical edition of Beckett’s short story ‘Echo’s Bones’ (Faber, 2014). He is currently preparing a critical edition of Beckett’s ‘German Diaries’ (with Oliver Lubrich; Suhrkamp, 2019).

Balazs Rapcsak is a doctoral candidate in Anglophone Literary and Cultural Studies and adjunct lecturer at the Department of English of the University of Basel. He works as an assistant in the Swiss National Science Foundation project “Beckett’s Media System: A Comparative Study in Multimediality.” Combining different strands of media theory with traditional Beckett criticism, his current research explores the interrelatedness of Beckett’s output in various media. He recently published “Switching Attention: Technologies of Awareness in Beckett’s Krapp’s Last Tape.” The Arts of Attention. Ed. Katalin Kállay et al. Paris-Budapest: L’Harmattan, 2017. 457-468.

Armin Schäfer is Professor of German Literature at the Ruhr University Bochum. His research priorities include the relationship between literature and the history of science and the literary and media history of the 20th century. He has published a book on Stefan George, edited a recent volume on Samuel Beckett, as well as on the history of psychiatry and on the melodrama, among other publications.

Philipp Schweighauser is Associate Professor and Head of American and General Literatures at the Department of English of the University of Basel. He has worked on a wide variety of issues in American Studies, but his main foci are 18th to 20th American literature and culture; literary, cultural, and media theory and history; literature and science; soundscape studies; life writing; and aesthetics. He is the author of The Noises of American Literature, 1890-1985: Toward a History of Literary Acoustics (UP Florida, 2006) and Beautiful Deceptions: European Aesthetics, the Early American Novel, and Illusionist Art (U of Virginia P, 2016). He is the principal investigator of two Swiss National Science Foundation projects: “Beckett’s Media System” and “Of Cultural, Poetic, and Medial Alterity: The Scholarship, Poetry, Photographs, and Films of Edward Sapir, Ruth Fulton Benedict, and Margaret Mead.” Schweighauser is currently serving as the President of the Swiss Association for North American Studies.

Dirk Van Hulle, professor of English literature at the University of Antwerp and director of the Centre for Manuscript Genetics, recently edited the new Cambridge Companion to Samuel Beckett (2015). With Mark Nixon, he is co-director of the Beckett Digital Manuscript Project (www.beckettarchive.org) and editor-in-chief of the Journal of Beckett Studies. His publications include Textual Awareness (2004), Modern Manuscripts (2014), Samuel Beckett’s Library (2013, with Mark Nixon), James Joyce’s Work in Progress (2016) and several genetic editions in the Beckett Digital Manuscript Project, including Krapp’s Last Tape / La Dernière Bande, Molloy (with Magessa O’Reilly and Pim Verhulst), L’Innommable / The Unnamable (with Shane Weller) and the Beckett Digital Library.

Pim Verhulst is a postdoc at the University of Antwerp. His research focus is genetic criticism, audionarratology, (late) modernism and radio drama. He has published articles in Genetic Joyce Studies, SBT/A and JOBS, of which he is an assistant editor; and chapters in Beckett and BBC Radio (Palgrave, 2017), Beckett and Modernism (Palgrave, 2018) – co-edited with Dirk Van Hulle and Olga Beloborodova – and Audio-narratology: Lessons from Audio Drama (Ohio State UP, 2019). As an editorial board member of the BDMP he has co-authored the modules on Molloy, Malone meurt / Malone Dies and En attendant Godot / Waiting for Godot (with Dirk Van Hulle and Magessa O’Reilly). His monograph, The Making of Samuel Beckett’s Radio Plays, is appearing with Bloomsbury in 2019 and for Edinburgh University Press he is finishing a monograph on Samuel Beckett and the Radio Medium.

Beckett and the Media ¦ Venue

The conference takes place at the Hotel Klosterhotel Kreuz in Mariastein. The venue can be reached thus from Basel airport and Basel’s two train stations.

from Euroairport Basel-Mulhouse-Freiburg:

https://goo.gl/maps/3syPEZXF2ky

Once you’ve arrived at Euroairport, exit the airport and walk to the bus station, which is right opposite the airport entrance. Buy a full-price ticket for 5 zones (5 Zonen). Take (green) Bus 50 direction Bahnhof Basel SBB. Get off at Bahnhof Basel SBB. You can see the tram stops as you get off the bus; the are about 50 meters in the direction of your arrival. Take (yellow) Tram 10 direction Rodersdorf. Get off at Flüh, Bahnhof. Take (yellow) bus 69 direction Burg im Leimental. Get off at Mariastein Klosterplatz. As you get off the bus, walk 100 meters in the opposite direction. You’ve arrived at the venue, Kurhaus Kreuz, Mariastein.

from Basel SBB (Swiss train station):

https://goo.gl/maps/SFzpAJZ1nHE2

Once you have arrived at Bahnhof Basel SBB, exit the train station. The tram stops are right opposite the main entrance to the station. Buy a full-price ticket for 4 zones (4 Zonen). Take (yellow) Tram 10 direction Rodersdorf. Get off at Flüh, Bahnhof. Take (yellow) bus 69 direction Burg im Leimental. Get off at Mariastein Klosterplatz. As you get off the bus, walk 100 meters in the opposite direction. You’ve arrived at the venue, Kurhaus Kreuz, Mariastein.

from Basel Badischer Bahnhof (German train station)

https://goo.gl/maps/XizRL5GQ7p22

Once you have arrived at Basel Badischer Bahnhof, exit the train station. The bus stops are to your left as you exit the station. Buy a full-price ticket for 4 zones (4 Zonen). Take (green) Bus 30 direction Bahnhof Basel SBB. Get off at Bahnhof Basel SBB and walk 50 meters in the opposite direction. The tram stops are right opposite the main entrance to the station. Take (yellow) Tram 10 direction Rodersdorf. Get off at Flüh, Bahnhof. Take (yellow) bus 69 direction Burg im Leimental. Get off at Mariastein Klosterplatz. As you get off the bus, walk 100 meters in the opposite direction. You’ve arrived at the venue, Kurhaus Kreuz, Mariastein.

Beckett and the Media ¦ Sponsors

The organizers would like to thank the following institutions for their generous financial support:

|

|

|

Ressort Nachwuchsförderung |

|

|

|

|

Beckett and the Media ¦ Contact

Please direct all inquiries to beckett-media-english@unibas.ch.